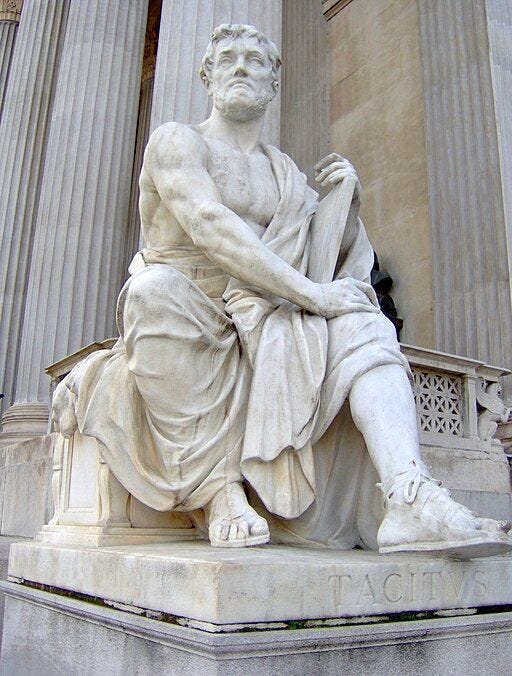

Since I have already read the “Complete Works of Tacitus” published by The Modern Library, I found that it was not a hassle to re-read the smallest sections within that compilation.

*** EDIT: I have been convinced to participate with next month’s books, so I apologize for the further miscommunication.

Thank you, and Hail Victory, always. o///

Tacitus is honored and well-loved by modern Aryans for good reasons: his extensive accounts concerning the Germanic tribes are well-written and inspiring, but more prudent than that, his works are a major supporting piece for countless archaeological and genetic findings from the modern era. His works stand the test of time due to the accuracy of his accounts, and therefore the basis of my report will be to compare what he says about Germans (and Britons) and their interactions with Romans. From the notes in my copy of “the Complete Works of Tacitus” and from the scant reading I have done online concerning Tacitus, it would seem that there is a lot to be said concerning the purpose and effects of his writings on the Roman public and intelligentsia.

*** I should note that I am not a philo-Roman, and therefore some of my views will go against those held by Tacitus, or at least I will go into greater detail since I live in a later century than he did and have the benefit of modern studies and hindsight. Tacitus was a Roman related to the famous men of his nation, and therefore he will speak more kindly towards his kindred at times, to the detriment of the historical record; I am an American related to Texan Scots descended from famous Gaels, and therefore I will speak more kindly towards my kindred at times where I could be more forcefully clear and forthcoming. I cannot ignore these biases from Tacitus, and I had to it make clear that I hold opposite biases. I do not begrudge Tacitus his bias, but instead commend him for being so ardently tribal and I excuse him for speaking poorly towards my own ancestors.

To quote from Tacitus in his opening paragraphs of “Agricola”:

Meanwhile, this book, intended to do honor to Agricola, my father-in-law, will, as an expression of filial regard, be commended, or at least excused.

Agricola:

Tacitus describes Britain and her tribes in a curious, yet refreshing way, quoting from older scholars that the shape of Britain is that of an axe, or an oblong shield, but with Scotland jutting upwards like a spearhead. I quite like this visual of Britain, it is striking and poetic.

He gives Caledonians (northern Britons later associated with the Picts of Alba) a Germanic origin, while he gives the Silures (southern Britons associated with Cornubia) an Iberian origin, and he goes on to give a Gaulic or Irish origin to all other Britons. Such comments have reverberated throughout history, even reaching to the modern era where linguists try to connect Pictish words to a Germanic origin, and countless theories have been made concerning the Iberian and later Phoenician connection with south-western Britain.

Theories such as these have not yet broken through the common Gaulic origin that academics tend to fall back on when it concerns all Celts, but they should not be pushed out of hand. Alba is closer to Nordic and Germanic nations, Cornubia is closer to Iberia than the rest of Britain, and the Gauls were known to have travelled to Britain for trade and marriage. The fact that Irish Gaels colonized the western shores of Britain is well-covered, as Dal Riata and later Scotland would soon be firmly fixed in the ethno-genesis of the island. It is also known that the Phoenicians, who colonized Iberia and conquered some of the Celts there, were also mining for tin and copper in Cornubia. None of these tidbits are discounted by most scholars, but the overall understanding of the Britons has remained mysterious to most modern readers. The connections made by Tacitus concerning the original Celtic peoples of Britain do contain some elements of truth, which were proven with modern archaeological and genetic research.

It is well-known that the Celts are descended from the Bell-Beakers, a group of people who come from the Holland-branch of the Corded Ware Culture. The Corded Ware people are the Indo-European ancestors of the Germans, Nordics, and Celts. The Bell-Beakers, for whatever reason, left the Corded Ware culture and began to develop their own material culture while also conquering the remaining Neolithic peoples of Western Europe. Their graves and genetics have been found as far south as Iberia (Spain) and as far north as Ireland, and they conquered various Neolithic groups in all areas between. So, the idea that the ancient Britons were descended from swarthy Iberians, burly Germans, and lanky Gauls is quite accurate, however odd it may seem to the modern reader. Is it any surprise that Caledonians, the Bell-Beakers of Northern Britain, were more Germanic (Corded-Ware) than Bell-Beakers from Spain, who would’ve mixed more with the Neolithic and Bronze Age populations of Iberia? Is it any surprise that they traded with Iberians, Gauls, and Germans, their genetic cousins? No! It is to be expected.

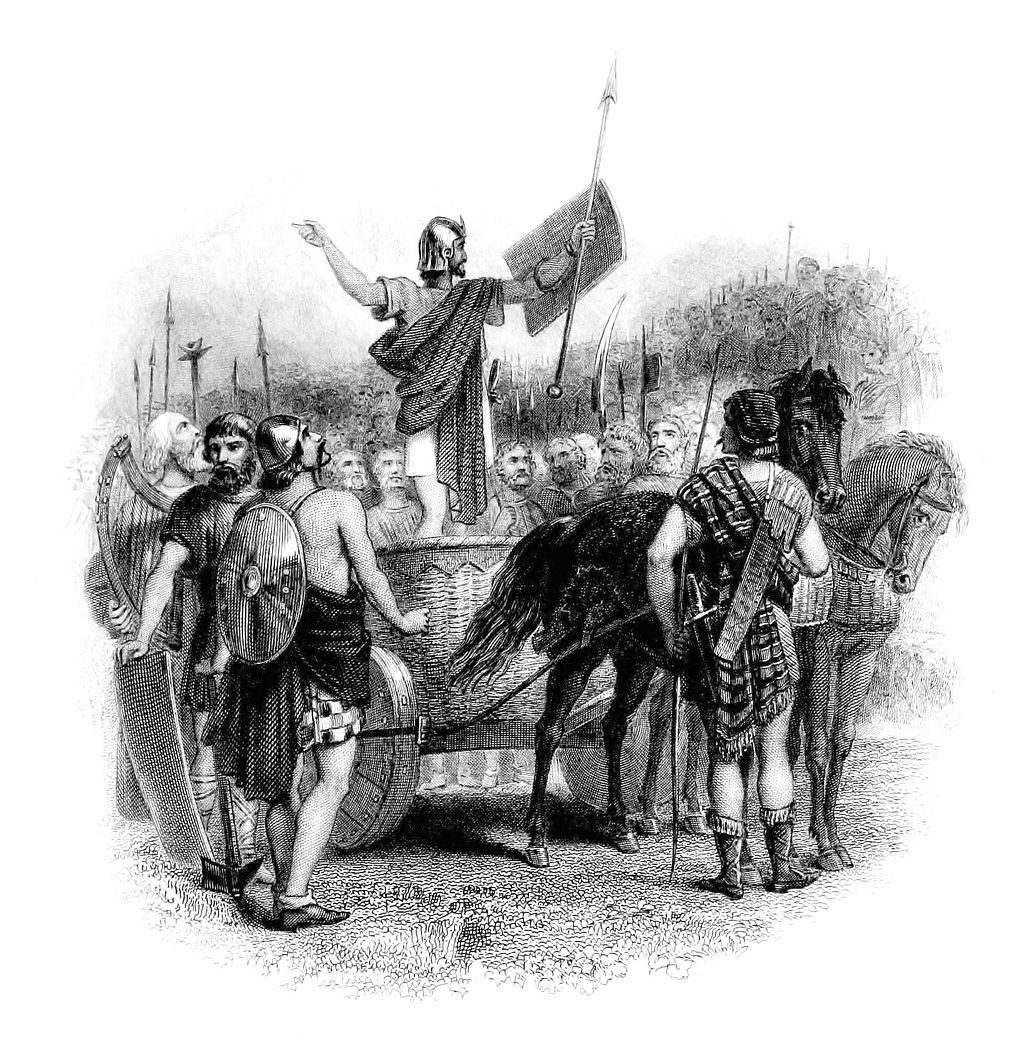

Tacitus also mentions that the Britons and Caledonians utilized chariots in their warfare. This curious fact is sometimes ignored by other scholars, mostly due to the fact that chariots were first fashioned on the steppe, and steppe-focused research is often tied to “racist Aryan theories of superiority”… The proto-Indo-Europeans created the chariot on the steppe, and their Indo-European descendants took it across the globe, including north-western Europe, regardless of what liberal scholars want to believe. Some scholars throughout history have tried to claim that northerly accounts of chariots are nothing more than the wet-dreams of Mediterranean-loving Northerners, which is ridiculous. Not only do chariots play a major role in Indo-European religions, with the sun and moon being pulled by special chariots and various Gods riding their own special chariots, but they are also seen a similar light to boats, being devices which can help ferry the dead to the Otherworld. Hence their usage in burials, just like boats. Just look at this Celtic chariot and try to say that we did not have chariots!

The text starts off with an account of Agricola’s early life as the son of a highly acclaimed Senator in Roman Gaul, then as a studious military apprentice in Roman Britain. I will not go into much detail here, as the text speaks for itself: Agricola was a skilled youth, with a bright future, and was born in a time where a virtuous man could flourish and claim for himself more glory than in other times. Britain was, according to Tacitus, in an excitable state of war, rife with colonial failures, and vengeful Celts intent on reclaiming their lost lands. A man like Agricola had ample opportunity to prove his merit and climb the ranks towards greater glory, and this example set forth by Agricola is one to emulate. Modern men are living in a time of great excitement, and we have the opportunity to “make a name for ourselves” if we have the will and ambition to do so.

The timeline of Agricola’s appointment as a military tribune between 58 - 62 A.D. aligns with Boudica’s Iceni Uprising which occurred in 62 A.D.. His participation in its suppression clearly played into Agricola’s rise to fame in the ranks of Roman society. That rebellion is famous in the stories of Roman Britain, and if the Reader is unaware of it, then I highly suggest learning about it. Not only does it show the strengths and weaknesses of the Celts, but it also shows the strengths and weaknesses of the Romans. According to Tacitus, Boudica was flogged and her two daughters were raped. She was a queenly woman and her daughters were nobility. This, along with other Roman tyrannies, led towards a bloody uprising which ended with the defeat of the Iceni and the semi-absorption of their kingdom into Roman Britain.

According to Tacitus, the Britons “admit no distinction of sex in their royal successions” and this curious statement really does not hold weight when scrutinized. Simply put: women in Roman society were not as capable of leading if there were no suitable men of noble stock, while Celtic women were quite capable of leading if there were no suitable men of noble stock. Irish and Scottish accounts of famous warrior-women are common, but these women generally rise to the occasion due to actions taken against their tribes, and there was no social stigma stopping them from doing this. Their husbands and noble kinsmen, either slain or useless, were sometimes shadowed by their noble efforts. In the example of Boudica, she enlisted the help of male nobles in her efforts, and she would not have been able to lead the tribes in battle if not for this simple fact.

With that said, it is clear that Celtic women were held in higher regard than Roman women, in their respective societies. This fact extended well into the modern era with the “pirate-queen” Grace O’Malley, who was capable of leading men, and yet who required the assistance of other powerful men. There were no Celtic matriarchies, but rather a form of tribal egalitarianism that allowed for noble women to act like stewards in highly critical situations of strife. There was no gender equality, for the amount of famous male nobles far outweigh the amount of famous female nobles, and there are even fewer famous warrior-women.

Another point to make here would be the curious assertation by various ancient writers that the Picts of Alba, who the Romans called Caledonians, were also recorded to have a female-based succession (matrilineally) for their nobles. The reason for this eludes scholarship, and it has been put forth that perhaps this was due to the Gaelic-Pictish alliance which stated that children born from Gaelic women and Pictish males would retain their status as the more noble line coming from the Gaels. Other reasons include fanciful accounts of them being matriarchal, or are somehow hilariously related to jews who also followed a form of matrilineal succession (children born to a jewish woman are jewish, regardless of the father).

There are no major studies on the subject of Pictish succession, because it is very vague, but suffice to say it has nothing to do with Semites like some crazed writers have suggested. A common point that has been made is that the Gaelic system of tanistry, where all male descendants of the royal line are suitable for kingship (as opposed to primogeniture) could be the source of this Pictish practice, thereby allowing sons of royal women to be available to the pool of potential royal successors. All that this really does is point out that women were viewed in Celtic society in a more noble light than in Roman society. Indeed, the Irish word for “wealth of ten cows” or “cumal” was the same word as a female slave, and such linguistic finds are rife throughout the Celtic languages. Women were clearly valuable to a society on the edge of the world.

Agricola returned to Rome and married a noblewoman, starting his familial line anew. He was promoted and later sent to Asia. When Nero was condemned as a traitor and the Year of the Four Emperors began, one of the contenders for the throne, Otho, murdered Agricola’s mother during one of his many sea-raids. This pushed Agricola into alliance with Vespasian, another contender of the throne and future emperor. This act alone brought Agricola into higher grades of Roman society, and allowed for him to remain powerful in a time where many of the Roman elite lost their power. Once again, Agricola showed that he was ambitious and strong-willed, with a mind towards tactical longevity.

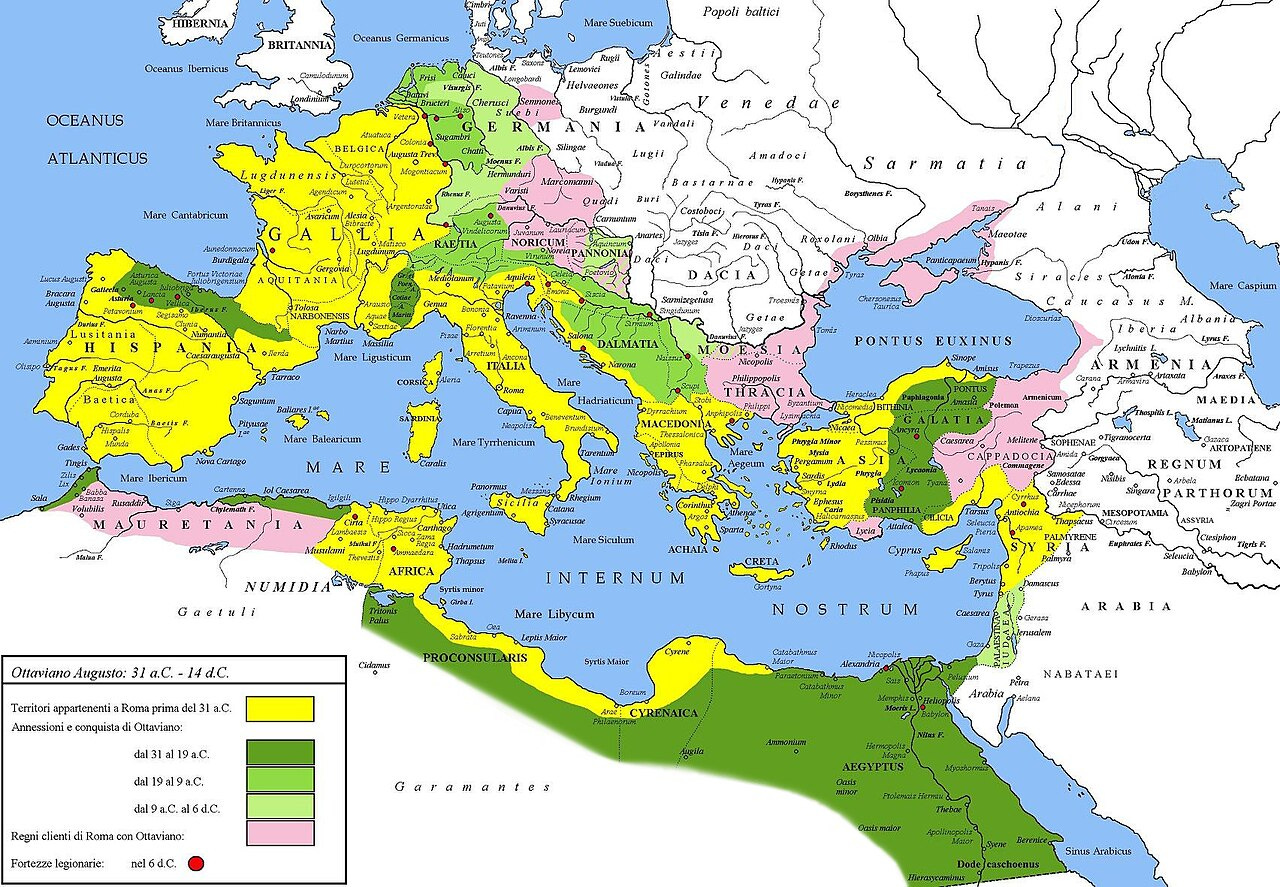

Agricola was sent back to Britain, this time as governor. He proved himself worthy of the honor, as shall be seen. Britain rebelled during the confusion of the Four Emperors, and Agricola was hard-set to bring things back into focus. Agricola pacified his own corrupt colonial centers and immediately pushed north in southern Caledonia where he set up new forts and made new allies with the British nobles, a campaign that was meant to happen earlier if not for the Uprising of Boudica. Tacitus rightfully points out that this tactic of Romanizing the British elites was to engender greater feelings of comradery between the natives and the Romans, which indeed assisted Agricola and his successors greatly; perhaps this careful tactic was conceived through experience after seeing the Britons rebel under Boudica, a rebellion caused by the heavy-handedness of the Romans.

I should point out that Romanized Celts made up a significant part of the Roman invasion force, and this would have put an additional element of fear into the Caledonians. The sheer magnitude of manpower required for this effort is impressive, let alone the fact that Agricola was victorious in many of his efforts. Simply imagine for a moment: you are a Caledonian of Pictish stock. Rome is a distant threat far away in a foreign realm called Italy, it is so far away that even dreaming of it is impossible. Your southern kindred have lost countless battles against the new enemy, but as of yet, your lands are untouched. Suddenly, during a time when Rome seemed weak, there comes marching an unstoppable force of Roman legionaries. They do not march alone without supplies, but are supplied by the might of the Roman navy. They do not march with Romans, alone but with subdued and converted Celts and Germans, these cousins marching in the vanguard against you, being led personally by their famous general, Agricola. Your kings and chiefs struggle to obtain unity among themselves to fight this new threat, and the only chieftain capable of uniting the folk disappears after the largest battle ends in your defeat. It would seem as though your whole world was crashing down.

It must have been a terrifying and glorious war for freedom and conquest.

Some have claimed that Agricola supported an exiled Irish prince and even provided troops for the effort to reclaim his throne. Now, this is only vaguely mentioned by Tacitus, but there are some points to be made here. The wording in ancient sources make it out to be less of a direct military campaign, but more of a material support in the form of soldiers and supplies. The prince in question is probably Tuathal Techtmhar, who was exiled to the Gaelic-colonized lands of early Dal Riata (the Hebrides). As can be seen using the map above, Agricola did indeed make headway into the Hebrides and would have descried Ireland across the strait on a clear day. Tacitus gives no information concerning this subject beyond mentioning that Agricola made alliance with an exiled Irish prince in hopes of using him to conquer Ireland. Therefore we are forced to look to Irish sources, which leave much wanting.

Tuathal, like a few other Irish Kings, are recorded to have reclaimed and conquered all of Ireland after their exiles. This is a common motif, and usually what the Irish scribes mean when they say “conquered all of Ireland” is just that they fought many battles and subdued their main enemies. Generally speaking, if a tribe or clan conquered the holy lands of Tara, then they were considered to have been Kings of a great nature, sometimes even considered to be High Kings even if they never subdued the entire island. This applies to Tuathal no less than others.

Claims that Romans never came to Ireland have been questioned lately, due to findings near to Tara which point to some form of direct contact. Some have claimed this was purely trade, others make the case for military contact, but the fact remains that ancient sources speak of Roman interaction in Irish affairs during the time of Agricola. Therefore, it is likely that Agricola did indeed utilize Hebridean Gaels against Irish Gaels to some degree, but this is such a vague piece of history that it is likely we will never learn anything more.

Agricola’s campaign in Caledonia truly only came to an end after the Caledonians were forced away from the Lowlands. The Caledonians were led by one Calgacus, who was likely supported as Over-King by various Caledonian tribes due to the continued loss of their southern lands. Such High Kings have existed before, generally chosen as war-leaders who retained their positions after the conflicts were over, similar to Caesar himself in this regard. Calgacus’s efforts to stop the Roman advance were futile, but his efforts did cause Agricola to pull back and regroup, an action which allowed for the Caledonians to regroup and re-establish their footing in the Lowlands. Ultimately, Agricola was only able to bleed the Caledonians, while also conquering their weakened southern kindred, and the disappearance of Calgacus did not stop Caledonian resistance.

Here is a section of the supposed speech given by Calgacus, according to Tacitus:

Whenever I consider the origin of this war and the necessities of our position, I have a sure confidence that this day, and this union of yours, will be the beginning of freedom to the whole of Britain. To all of us slavery is a thing unknown; there are no lands beyond us, and even the sea is not safe, menaced as we are by a Roman fleet. And thus in war and battle, in which the brave find glory, even the coward will find safety. Former contests, in which, with varying fortune, the Romans were resisted, still left in us a last hope of succor, inasmuch as being the most renowned nation of Britain, dwelling in the very heart of the country, and out of sight of the shores of the conquered, we could keep even our eyes unpolluted by the contagion of slavery. To us who dwell on the uttermost confines of the earth and of freedom, this remote sanctuary of Britain's glory has up to this time been a defense. Now, however, the furthest limits of Britain are thrown open, and the unknown always passes for the marvelous. But there are no tribes beyond us, nothing indeed but waves and rocks, and the yet more terrible Romans, from whose oppression escape is vainly sought by obedience and submission. Robbers of the world, having by their universal plunder exhausted the land, they rifle the deep. If the enemy be rich, they are rapacious; if he be poor, they lust for dominion; neither the east nor the west has been able to satisfy them. Alone among men they covet with equal eagerness poverty and riches. To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace.

Now, this speech is likely entirely made up by Tacitus, but it shows how the Romans viewed the Celtic response to their aggressions. I found this to be the most fascinating bit of information out of all of the information relayed by Tacitus in his account of his father-in-law’s life. There are more than a few quotes by Tacitus showing that Romans considered Celtic freedom as deeply opposed to Roman civilization. I often think about this rousing speech now that a more tyrannical empire is rising in the world. If I could have my way, I would prefer Roman rule over Israeli rule. If I could really have my druthers, I would deign to choose Indo-European supremacy over semitic domination.

Agricola was recalled to Rome, probably due to political strife coming from Emperor Domitian who was jealous of the accomplishments of Agricola in comparison to his minor triumphs against the Germans. Some even claim that Domitian poisoned Agricola, since Agricola died of sudden sickness when he was in his mere fifties. I do not see how a forceful man who led his own men in battle could die at fifty without some sort of long-standing health issue (which was never mentioned) or unless he was poisoned. Tacitus himself alludes to this poisoning.

Now, Tacitus claimed that Agricola “subdued the whole island” which is ridiculous. The Hebrides were never colonized, the northern Lowlands were never colonized, and the Orkneys were also never colonized let alone the other western isles, although Agricola likely received nominal and expected overtures of Celtic allegiance to Rome from various Caledonian tribes. Agricola only struck a dagger into the Caledonian lands, a dagger his successors could not keep in place, something later dynasties from England would soon learn. Over time, famous Roman walls and fortifications were built in an attempt to hold the Caledonians back, and the Gaelic invasion of the Hebrides and the western coasts of Britain continued. Rome was unable to obtain ownership of the entire British Isles, and they were unable to conquer the Germanic tribes. Thus, the Great Barbarian Conspiracy was capable of reclaiming most of Roman Britain only a couple of hundred years later, and the Gaels, Welsh, Picts, Frisians, Jutes, Anglos, and Saxons were able to replace the Romans across Roman Britain over the ensuing decades after the Great Barbarian Conspiracy.

Tacitus also claimed, along with most other Roman writers, that whenever battle occurred, the Celts would lose thousands of warriors while the Romans would only lose a few hundred. This motif plays out across the northern world, where Germans are also said to lose thousands of warriors when battling against a much smaller Roman force. I am doubtful of such claims, and so are many learned scholars. The known battle-sites between Celts and Romans do not show such claims to be veritably true. We can forgive Tacitus for such erroneous claims: he was a member of a mighty militaristic empire, and he was proud of it, and that is not only to be expected, but to be praised. The Irish scribes did the exact same thing when they recorded inter-Gaelic wars, and they did this to uplift and glorify those they served, their chieftains and tuath. Tacitus did this to uplift his father-in-law, and I can respect that.

Perhaps Britain would’ve been fully conquered if Agricola had been allowed to stay in Britain and if he had been given full authority in northern campaigns then Germany mighty also have been taken; surely he was uniquely suited to the task, but this did not happen. Therefore, Tacitus simply gives credit to his kindred where there is no credit due; the only credit that can be given is honorable acceptance that Agricola made headway into far northern lands, lands far from Rome, lands unfriendly to the Roman, in a time of great imperial turmoil.

Personally, I think we can learn a great deal from Agricola’s tactical perseverance and his ambitious rise to power which came from allying himself to goodly and virtuous Romans. This was a man who could achieve greatness through his own willpower, and it would be wise if we emulated this in the coming times of strife in our failing American Empire.

Hail Agricola!

Germania:

This text is one of the primary supporting texts used by modern archaeologists and linguists when trying to determine the history and origin of the Germanic tribes of the Iron Age. The text itself was largely forgotten until the Renaissance, and was only sparsely utilized by medieval Christian scholars. It was resuscitated during the period of Germanic unification and was further revived by Jacob Grimms when he started the true scholarly study on Germanic peoples. In the modern era there have been liberal scholars who fancy that the text is entirely made up, or they tend towards a view that the text espouses false ideals concerning the “noble savage” which is hilarious. From Wikipedia:

Because of its influence on the ideologies of Pan-Germanism and Nordicism, Jewish-Italian historian Arnaldo Momigliano in 1956 described Germania and the Iliad as "among the most dangerous books ever written".[9][10]

If a jew thinks it is dangerous to read these books, then we must read them and wash our minds of the Torah and Testament. As can be seen with this Harvard article, liberals HATE this book, therefore, we must love and cherish it.

First off, a list of quotes I found to be most fascinating:

To give ground, provided you return to the attack, is considered prudence rather than cowardice.

They choose their Kings for birth, their generals for merit. These Kings have not unlimited or arbitrary power, and the generals do more by example than by authority.

They (women and children) are to every man the most sacred witnesses of his bravery - they are his most generous applauders.

They even believe that the sex (women) has a certain sanctity and prescience, and they do not despise their counsels, or make light of their answers.

Then the King or chief, according to age, birth, distinction in war, or eloquence, is heard, more because he has influence to persuade than because he has power to command. If his sentiments displease them, they reject them with murmurs; if they are satisfied, they brandish their spears. The most complimentary form of assent is to express approbation with their weapons.

They transact no public or private business without being armed. It is not, however, usual for anyone to wear arms till the state has recognized his power to use them.

It is no shame to be seen among a chief’s followers. - It is an honor as well as a source of strength to be thus always surrounded by a large body of picked youths; it is an ornament in peace and a defense in war.

Their marriage code, however, is strict, and indeed no part of their manners is more praiseworthy. Almost alone among barbarians they are content with one wife…

Clandestine correspondence is equally unknown to men and women.

To the practice of usury and of increasing money by interest, they are strangers; and hence is found a better guard against it, than if it were forbidden.

Tacitus accurately explained German society, religion, and tribal makeup, although this is all parsed heavily through the Interpretatio Romana, which is a process of religious analysis done primarily by Greeks and Romans wherein they would ascribe Greek or Roman Gods to barbarian Gods. This system of religious interpretation is incredibly perennial, a study of religion that says that the Gods are divine internationalists with clear parallels in most cultures, and with common origins and roots. I personally think such associations are esoteric, and that they have generally have little bearing on the real histories of such deities. With that said, there is much to be gained by understanding how the Romans viewed barbarian Gods, and this is not just due to the fact that our Gods are indeed descended from the same Indo-European sources, but also because divinity, if it be true divinity, will often express itself in the same ways. Thus, the Interpretatio Romana is incredibly perennialist in nature.

For example, when Tacitus claimed that the Germans sang about Hercules before any other hero when they went into battle, we are not to assume that they actually worshipped Hercules. Instead, we are to logically deduce that the Roman scholars interpretated Thor, another bludgeon wielding God, as being the same divine being as Hercules. When Tacitus said that Mercury is their chief god, we must realize that he is speaking about Odin, who was often associated with Mercury and Hermes by the Romans and Greeks.

When Tacitus said that the Germans worship an earth god Tuisto and his son Mannus, who likewise has three sons who go on to be the ancestors of three Germanic tribes, we find a curious interpretation of Germanic myth. For example, Tuisto is likely a reference to Tiwaz, or Tyr, and his son Mannus is likely a reference to an earlier Indo-European ancestor who is preserved as Manu (Indo-Aryan) and Manannan mac Lir (Gaelic). Mannus’s three sons being the ancestors of all Germans are clearly utilized by later scholars when writing about Germanic history, such as Jordanes, along with the Gesto Danorum.

Tacitus mentioned multiple times the odd practice of Germanic tribes fighting directly with women in their ranks, or with women following the train in a lagging fashion. This was mentioned by Caesar during his war against the Suevi and their leader Ariovistus. This was mentioned by Roman historians who recorded the earlier Cimbrian Invasion. This was mentioned by Tacitus multiple times. Therefore, we must examine this curious trait. It reminds me very much of the Germans of World War 2, a terrible war where the Germans were pushed to the utter extreme and extinction. Just like the Germans of the Iron Age, modern Germans also fought with their women at their backs, with complete victory being the only assurance against their enslavement, rape, and murder at the hands of the enemy.

Personally, I find this way of fighting to be foolish, but it has clear parallels in Celtic and Scythian societies, and was utilized to great effect across the barbarian world. For example, when Agricola conquered the Lowland Caledonians, men and women committed suicide together rather than be enslaved, an act that was done by the earlier Cimbrians upon their failure. Also, when Scythian men did not return from war, the women would refuse marriage with foreign tribes and would defend their lands and children with ferocity until a suitable tribe of related men would appear, leading to the legends of Amazonian women-warriors. When your women are with you, in both body and soul, you fight harder, with more chances of a complete victory, a victory that immediately allows for settlement and colonization. However, it also allows for terrible defeats wherein the whole tribe is extinguished, and the women taken by the enemy. I do not know where the correct moral route lies in regards to this, but I can at least attest that warrior-women are more likely to defend themselves against tribal enemies, compared to house-wives who cannot lift a blade or shoot an arrow to stave off rape and enslavement. I think it would be prudent to think upon this, seeing as a more evil enslavement is being placed around our necks.

When Tacitus spoke about certain undesirable criminals being placed into bogs under a hurdle of stones, we know that he is identifying a real historical practice. There are many famous bog bodies, made famous due to the fact that the bodies and their clothes are so well-preserved in the bogs. Here are some bog bodies, some of which further prove that Tacitus spoke honestly concerning the Germans, such as the Suebian habit of tying their hair into a distinctive knot, or the red and blonde hair of the Germanic peoples.

When Tacitus spoke about their clothing style being mixed between trousers and cloaks, we know he spoke the truth due to the bog bodies and other clothing items found preserved in moors. They did indeed have pants and cloaks. Pants were first made on the steppe, to better facilitate horse-riding.

Tacitus did hilariously mention that prior to Roman interaction with the Germanic tribes, amber was not widely traded or known to have value. Hilarious! Amber was utilized wide and far in the Bronze Age, being a major component of Bell-Beaker and later Corded Ware cultures, with Baltic amber reaching far southern lands through trade long before Rome rose in glory. Clearly, Tacitus was unaware of the genetic and cultural connections between all Northern Europeans, which was common for Romans and Greeks to be confused about.

Tacitus mentioned that the famous Ulysses visited Germany during his journeys returning from the Trojan War. The highly controversial Oera Linda Book says as much, although it goes into greater detail. Concerning the Greek jaunt into Germany, the OLB has this to say:

After twelve years had elapsed without our seeing any Italians in Almanland, there came three ships, finer than any that we possessed or had ever seen.

On the largest of them was a king of the Jonischen Islands whose name was Ulysses, the fame of whose wisdom was great. To him a priestess had prophesied that he should become the king of all Italy provided he could obtain a lamp that had been lighted at the lamp in Texland. For this purpose he had brought great treasures with him, above all, jewels for women more beautiful than had ever been seen before. They were from Troy, a town that the Greeks had taken. All these treasures he offered to the mother, but the mother would have nothing to do with them. At last, when he found that there was nothing to be got from her, he went to Walhallagara (Walcheren). There there was established a Burgtmaagd whose name was Kaat, but who was commonly called Kalip, because her lower lip stuck out like a mast-head. Here he tarried for years, to the scandal of all that knew it. According to the report of the maidens, he obtained a lamp from her; but it did him no good, because when he got to sea his ship was lost, and he was taken up naked and destitute by another ship.

Take it, or leave it!

There was a lot I wanted to say, but decided to leave out due to the length of this report, specifically a discussion on Germanic women, divination, and genetic relation to the Bastarnae and Sarmatae. Perhaps I will incorporate Tacitus into future reports and essays on those subjects, so stay tuned!

I hope I was able to accurately add worth to Tacitus’s words, to show that he was hitting the nail on the head, but that the nail can be driven further than what he accomplished. The Germanic tribes are truly glorious. When they are victorious, they represent the highest of our race, and yet when they fail they fall to the lowest of lows. We must redeem our bloodlines. We must redeem the Germanic race, and all Northwestern Europeans, and all Europeans, to our rightful place once more. We cannot be weak for much longer, lest we experience greater tragedies than ever before… Rome was a pleasant enemy compared to the one we face today. Let Rome be a lesson to us all, both in glorious deeds we should seek to emulate, and terrible wounds we should seek to avoid.

Hail Tacitus, and good-end. o///

Keep preaching brother

In “Mussolini as Revealed In his Political Speeches November 2914 – August 1923”, he shows himself to be vehemently anti-German and ultra chauvinistic in terms of Italy as the "new Roman Empire", while often quoting from Marx (being his core ‘philosophy’ at that time). I am sure he matured out of this ignorance once Hitler explained a few home truths, but it makes me want to look deeper into Mussolini. He is often misquoted and misjudged for all the wrong reasons. He does, to his credit, go on to acknowledge that “the workers” had been duped by the [jewish] Bolsheviks/communists in Russia.

In “THE FATAL VICTORY - Speech delivered at the Teatro Comunale, Bologna, 24th May 1918” Mussolini writes:

“The Russian experiment has helped us enormously, both from the socialist and the political points of view. It has opened many eyes which had persistently remained closed. It must be realised that if Germany wins, complete and certain ruin awaits us. Germany has not changed her fundamental instincts. They are the same as those which Tacitus describes to perfection in his Germania in these words: “The Germans do not live in villages, but in separate houses, set wide apart the better to protect them against fire. To shield themselves from the cold, they live in underground dwellings covered with manure or clothe themselves in the skins of small animals, of which they have a great number. Strong in war, but persistent drunkards and gamblers, armed with spears and well supplied with horses, they prefer to gain wealth, when it suits them, by violence rather than by the working of their lands.”

In his De Vita Julii Agricolæ this Roman writer notes a contrast between the Germans and the Britons nineteen centuries ago which is still the same to-day, that is, that while the Britons fight for the defence of their country and their homes, the Germans fight for avarice and lust. These same tribes, driven once to Legnano, have resumed their march beyond the Rhine and are preparing once more to take up the offensive against us. But the “lust” of which Kuhlmann speaks will not carry the Germans beyond the Piave.” [end quote]